Articles

Beyond the Mustard Jar: An intriguing tale of vegetable evolution

In the realm of agriculture and horticulture, few plant families boast as diverse and culturally significant a lineage as the Brassicaceae family, commonly known as the mustard family or your beloved cruciferous vegetable. Among its esteemed members are some of our most consumed vegetables, including cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, kale, and Brussels sprouts, just to name a few. Yet, beyond their culinary prowess, the origins of these Brassica species plants hold a rich tapestry of history, migration, and both ecological and human ingenuity.

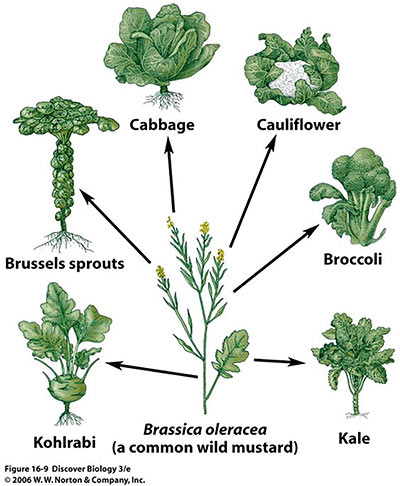

To truly appreciate the origins of Brassica species plants, we must journey back through the annals of time, tracing their roots to the wild mustard plant (Brassica oleracea) native to the Mediterranean region, now commonly seen growing roadside in fields and ditches on almost every continent. These wild ancestors, with their small, bitter leaves and pungent flavor, were a far cry from the diverse array of vegetables we know today. However, they served as the foundation upon which centuries of human cultivation and selection would build.

The domestication and cultivation of Brassica species plants hold profound cultural significance across civilisations. Ancient Greeks and Romans valued cabbage not only as a culinary staple but also for its medicinal properties. In China, broccoli and bok choy have been cultivated for thousands of years and hold valuable places in traditional cuisine. Similarly, kale, with its robust flavour and nutritional density, has been a dietary staple in Europe since ancient times. The story goes seeds were scattered by missionaries across the Americas to mark the path they'd travelled by creating a yellow brick road. These happy plants soon spread and now occupy vast acres of land, considered an invasive weed in some areas.

The transformation of wild mustard plants into the myriad Brassica species we know today is a testament to the power of human ingenuity and selective breeding. Over generations, natural selection from winds and animals helping to cross-pollinate and farmers and horticulturists selectively breeding plants with desired traits, such as larger leaves, tighter heads, or sweeter flavour, gradually shaped the Brassica species into the diverse array of vegetables we enjoy today. This process, known as domestication, has yielded countless cultivars and varieties, each with its own unique characteristics and culinary uses.

This is different to GMO, let me explain how. The superiority of selective breeding over genetic modification lies in its reliance on natural processes and the preservation of genetic integrity. Selective breeding harnesses the inherent diversity within a species, allowing for the gradual enhancement of desirable traits through controlled breeding and natural selection. This method respects the natural boundaries of genetic variation and avoids the introduction of foreign genetic material.

In contrast, genetic modification involves direct manipulation of an organism's genome in a controlled laboratory setting, often by inserting genes from unrelated species. While genetic modification can produce rapid changes and introduce novel traits, it carries inherent risks and ethical concerns. Manipulating the genetic code in this manner may disrupt the delicate balance of ecosystems, pose unforeseen risks, and raise questions about long-term environmental impact and biodiversity.

Furthermore, selective breeding aligns with traditional agricultural practices and has been used for millennia to improve crop varieties. It offers a time-tested approach that respects the natural evolution of species while empowering growers to achieve desired outcomes through careful selection and breeding techniques.

How exactly does this work?

In the farmer's plot, where rows of crops sway to the rhythm of the wind, two hearty plants catch his discerning eye. Their stoic stems, steadfast against the whims of nature, beckon with a promise of resilience. Intrigued, the farmer embarks on a subtle experiment, bringing these botanical guardians together in a careful union through cross-pollination and preferentially saving seeds.

As seasons unfold, a new generation emerges, bearing the subtle imprint of their resilient ancestors. Their stems, fortified by the silent wisdom of generations past, stand firm against the relentless onslaught of wind and weather. This act mirrors the age-old principles of evolution pondered by Darwin—the essence of selective breeding echoing the intricate dance of natural selection.

For Darwin, nature's theater was a grand stage where each organism faced a chorus of challenges. Those best equipped to adapt emerged victorious, their traits etched into the pages of evolutionary history. In the farmer's field, amidst the rustling leaves and whispering winds, lies a microcosm of this timeless saga—a testament to the enduring power of adaptation. Survival of the fittest, is what we usually call it.

However, looking closer, in the case of Brassica species, it was survival of the heftiest flower buds to create the broccoli and cauliflower. Survival of the most dense terminal bud, to create cabbage. Survival of the largest leaves, to create kale. Survival of the best roots, to create turnip. And so on.

Read Charles Darwin's fascinating work on variation through domestication here.

Despite their varied appearances, many Brassica species plants share a remarkable genetic similarity, a testament to their shared ancestry. In recent years, advances in genetic sequencing have shed light on the intricate relationships between different Brassica species, revealing a complex web of genetic diversity and interbreeding. This genetic diversity underscores the resilience and adaptability of Brassica species plants in the face of environmental challenges and their ability to become locally adapted to almost any environment.

The story of Brassica species plants serves as a reminder of the profound impact that human intervention can have on the natural world. Yet, it also offers hope and inspiration for sustainable agriculture and biodiversity conservation. This story has been echoed in many other plants. Corn, for example, was a tall nothing-much-to-speak-of grass with a handful (if you were lucky) of hard seed heads. Apples started as small, bitter, not very juicy crab apples.

The story of Brassica species is a tale of innovation, adaptation, and cultural exchange that spans millennia. From their humble origins in the Mediterranean to their global proliferation and culinary acclaim, these remarkable plants embody the intricate dance between humans and the natural world.

Remember, if you want to selectively breed your own Brassica, tolerant of your unique climactic conditions, you'll need to save the seeds from your favourite plants. Which means not eating them! Here are some easy tips to follow when preferentially saving seeds:

- Plant multiple plants close together for cross-pollination.

- Only grow one type of Brassica oleracea at a time to avoid cross-breeding.

- Choose the best plant and don't harvest its head (hard when it looks so tasty!).

- Let the pods dry on the plant until they turn yellow.

- Cut the plant, hang it upside down to dry for 1-2 weeks.

- Crush the dry pods to release the seeds.

- Separate seeds from chaff using winnowing or a screen.

- Store seeds in a cool, dry place; they remain viable for about five years.

Now, which Brassica species will you be growing in your garden this season?